Every part every interval (EPEI) is my favorite lean metric for high mix/low volume (HMLV) value streams and probably the least known. It’s especially helpful when changeovers are a significant portion of capacity as frequently is the case with machine-oriented operations.

As the title implies, I want to share how I’ve used EPEI in lean transformation rather than establish its usefulness or provide the math. These are snippets of how I’ve used and adapted EPEI to address the challenges of high mix/low volume value streams – more to get you thinking than to be exhaustive.

Favorite Non-math Definition of EPEI. EPEI is the time it takes to produce every member of a product family including the changeovers between products.

Planned EPEI. Much like takt time is a planning parameter used in the design of a future state, EPEI can be used in the same way. In HMLV operations, mix and volume can change radically, sometimes daily. I determine a Planned EPEI by taking representative mix and volume patterns from historical time periods and then calculating the EPEI for each time slice. Then we can make a decision about how much mix and volume we plan to support.

Dynamic EPEI. It’s all well and good to set a Planned EPEI for each process, but volume and mix changes all the time. I recalculate EPEI for each period using the expected mix and volume. That can be based on revised forecasts or actual orders. The idea of a dynamic EPEI supports the reality of varying demand patterns.

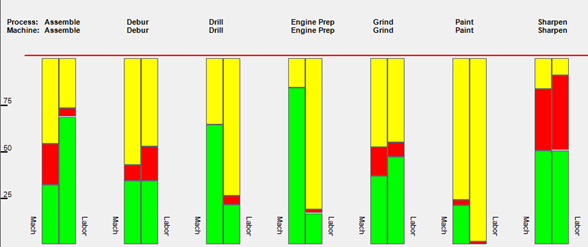

Using EPEI to Visualize Capacity. The ratio of the Dynamic EPEI to the Planned EPEI is then an expression of required capacity vs. planned capacity. Using a ratio allows a simple visualization of capacity requirements for a specific mix and volume across all processes in a value stream even when the Planned EPEI differs by process.

In this example, the red line at the top represents 100% of Planned EPEI. We split out productive (in green) from non-productive (in red) which includes changeover, downtime, yield loss, rework, load/unload. The remaining is available capacity (in yellow) and is what we tell our sales force to go sell. Just to complete the picture, we separate machine capacity from labor capacity.

Every Ordered Part Every Interval. The classic EPEI calculation assumes that all products are ordered for each period. When a value stream must support a collection of runners, repeaters and strangers, that’s not the case. The dynamic EPEI allows us to adjust the classic definition to “Every Ordered Part Every Interval”. When the value stream must support hundreds to thousands of product variants, clearly they aren’t all going to be ordered in every time period.

Different Types of Changeovers. Since EPEI is one of the few lean metrics that include changeover, it forces us to focus there. Not all changeovers are created equal. The normal changeover that we all think of is the time between when the last piece is produced to when the first good piece of the next product is produced. A second type of changeovers is what I’ve termed a “major changeover.” This is where there’s some additional changeover requirement for a group of products. This is reflective of pattern production. For example, in a paint line, there may be no or very low changeover between individual products of the same color but a longer changeover when a color change is required. Combining the concept of changeover groups with a preferred sequence of changeover groups allows sequencing - that could be from light to dark, wide to narrow, thick to thin, lower temperature to higher temperature, whatever. The third type of changeover is what I call a “useful life” changeover. That may reflect tooling wearing down, chemicals being depleted, or maintenance requirements.This is a changeover that may occur even within a longer run of the same product. I’ve seen these kind of changeovers be driven purely by time but also by quantity. For example, one machine must be re-calibrated and cleaned every 8 hours regardless of what was run but another machine must have tooling changed out every 15,000 strikes.

EPEI and Fixed Interval Scheduling. EPEI sets the time period for heijunka scheduling or fixed interval scheduling. In this approach, we plan to run our operation in a series of fixed schedules of the same length. My starting point typically is to set a target of a week but want to move to as short a period as can be sustained.That would be the Planned EPEI. Then as actual orders come in, we use the Dynamic EPEI to determine whether a period is oversold or undersold and invoke our buffering strategy to match capacity to actual order requirements. If we have a finished goods supermarket and are oversold, then we use our capacity to build what we can and pull the rest. Similarly, if we are undersold and have available time, then we can use that time to replenish the supermarket to targeted stock levels.

By running with fixed length intervals, we can move beyond a simplistic EPEI formula that requires you to provide a planned number of changeovers needed to a more comprehensive approach where the number of changeovers and the types of changeovers can be specifically determined in advance.

Driving EPEI for Continuous Improvement. The goal is to reduce EPEI to as low a level as possible. This moves us closer to our ultimate goal of one-piece flow. We want to use all of our available capacity to run as many changeovers as possible so we can reduce our batch size as low as possible and free up as much inventory as possible. So we can use SMED to drive to setup reduction, or TPM to reduce downtime, or 6Sigma to reduce defects. Since EPEI is a composite of a number of performance factors, anything that improves a factor contributes to its reduction. An orientation to reducing EPEI is a useful strategy in our quest for perfection.

If it isn’t obvious by now, software support for all of this is absolutely essential. High mix/low volume value streams are awash in data. Software is beginning to emerge that helps manage the variation and complexity found in real world operations.

_______________________________________________________________

This post was authored by Phil Coy, Managing Director, Strategic Services for mcaConnect responsible for the Manufacturing Excellence practice. His professional experience of over 30 years includes more than 25 ERP implementations and over 13 years of lean experience, Phil specializes in high mix/low volume lean implementation and complex manufacturing. He is the designer of mcaConnect’s Areteium lean transformation software supporting future state design, modeling and planning for complex manufacturing. Integrating standard lean principles and tools with ERP solutions and then extending them to support increasing variation and complexity are his passion. His industry experience includes industrial equipment, specialty metals, chemicals (process), electronics, medical devices, food and beverage, and consumer packaged goods. Phil blogs at www.mcaconnect.net/blog.