I recall my first encounter with my sensei, many, many years ago. I expressed amazement that he could so quickly observe processes and discern waste and opportunities. He assured me that, with practice, I would be able to do the same. At the time, it seemed like he was being nice or at least extremely overoptimistic. Fortunately, he was right.

The Traditional Ohno Circle

My initial practice was largely comprised of lots and lots of kaizen. This required a tremendous amount of direct observation. My observations were often assisted by things like time observation forms and spaghetti charts to facilitate focus and structure, without which my effort could quickly devolve into industrial tourism (hey, look at the wild tattoo on the operator’s arm!).

My awareness development was supplemented by the occasional Ohno circle exercise. The sensei would require me to watch a designated area and all that was happening or not happening within it. He then hit me with Socratic questions, quickly exposing my limited power of observation and intellectual curiosity (What did that operator do? How repetitive or cyclical was it? What is the standard? What was the cycle time(s)? What is the standard WIP?, Why did the operator do such and such? Etc.) Eventually and painfully, I honed the discipline and ability to “see.”

Insufficient Awareness and the Need for Two More Circles

But my awareness revolution, to use Ohno’s term, was limited in scope. It was applied to processes that pertained almost exclusively to work, or in support of work - fabrication, assembly, call centers, underwriting, patient rooming, part kitting, etc. While it is necessary to be aware of these things, it does not represent sufficient awareness. In other words, if we are to be effective lean leaders there are other things of which we need to be aware.

Simply put, we need to see more and we need to see in a broader context. If we don’t, we risk restricting our insights to only processes and tools. That’s a dismal one-dimensional existence and will never lead to transformation.

As Peter Senge quoted the former Herman Miller CEO, Max de Pree, “The first responsibility of a leader is defining reality” (Senge, The Fifth Discipline, 353). “Reality” and “truth” are inextricably linked, with the latter meaning the conformance of the mind to the extramental reality. (Here, I am talking about logical truth, not moral truth.). If we don’t identify and understand the truth (aka current condition), along with its cause(s), it’s super hard to ever achieve the target condition. Similarly, it’s then near impossible to lead other folks to discover, see, and own the truth.

Other than process, what truth or reality must a lean leader care about?

Let’s start with basic lean principles like leading with humility, treating everyone with respect, having constancy of purpose, managing by results and means, developing organizational problem-solving and continuous improvement capabilities, and so on (see the Shingo principles and Liker’s Toyota Way principles). These principles were not invented per se, but rather discovered. They are fundamental truths that serve as the foundation for every sustainable operationally excellent enterprise.

Process, as described above, is important, but as leaders we also need to expand our awareness to encompass our own behaviors and those of others. Only then can we begin to live and coach others to live the lean principles and make helpful adjustments to the management system.

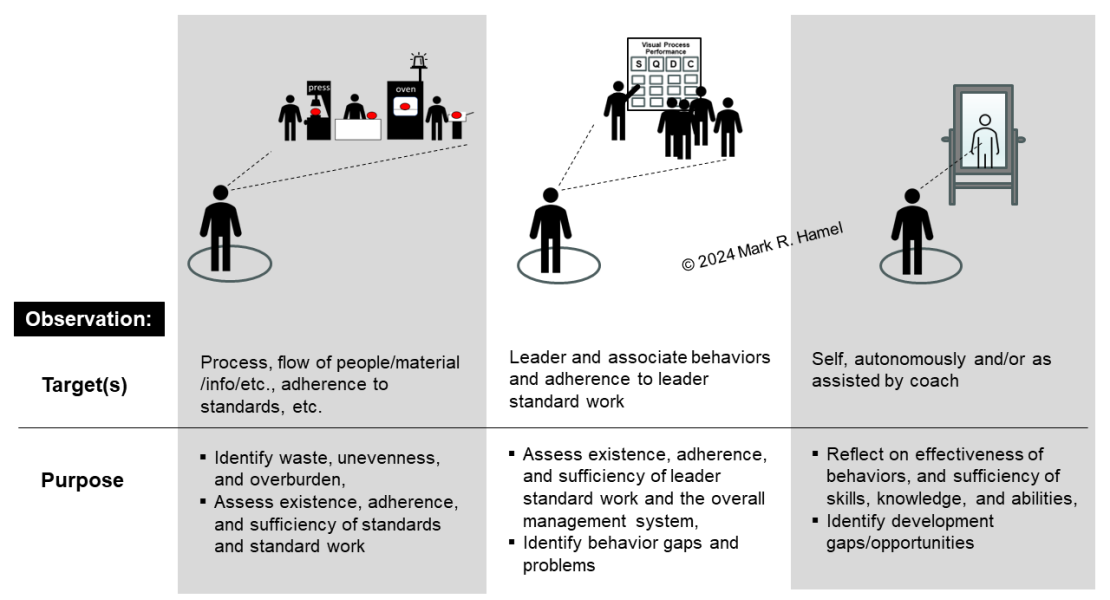

I have identified three categories of circles, see figure.

- Process. This is the traditional Ohno circle that lean practitioners have embraced. It encompasses awareness of processes, including the flow of people, material, tooling, supplies, and information, and the identification of waste, unevenness, and overburden.

- Leader and associate behavior. This circle overlaps the first and includes the application of SDCA (standardize-do-check-act), especially in the context of gemba walk leader standard work, covering leader checks of the existence of, adherence to, and sufficiency of process standards and standard work. Similarly, it includes observing leaders as they conduct their own leader standard work (gemba walks, huddles, one-on-ones, governance, etc.). The behavioral-oriented observation cycle provides the feedstock for coaching mindsets, assumptions, and ultimately behaviors. It also provides objective evidence from which we can engage in improving standards and standard work and identify and solving problems.

- Self. Leaders are responsible for their own self-development. This requires self-awareness, which can be facilitated through personal reflection, as assisted by coaches. Because the lean model is unapologetically one of leader-as-coach, the primary coach is usually the leader’s own boss (aka the leader’s leader). Know that self-awareness includes the internal (how we see ourselves) and external (awareness of how others see us).

Different Circles, Different Vision, and Different Subjects of Observation

The practice of the three circles is primarily about different subjects of observation, while using different lenses or observation paradigms. For example, we can observe something with the naked eye, or we can use binoculars to magnify the observable object, or we can use a thermographic camera to discern heat signatures, or an MRI machine to get detailed images below the surface. These are not mutually exclusive, we often can and should use more than one. Lean leaders must apply a kind of multi-vision to reach their full potential and that of their team. So, get in the circle…all of them.